If you’ve ever watched a 12-year-old shortstop rush a throw to second… spike it, watch it trickle into the outfield, and suddenly the inning turns into a track meet—you already know the lesson.

A double play is great.

But forcing a double play can be a rally starter.

In youth baseball (especially ages 8–14), the best teams usually aren’t the ones chasing the hardest play. They’re the ones that stack reliable outs and keep innings from snowballing.

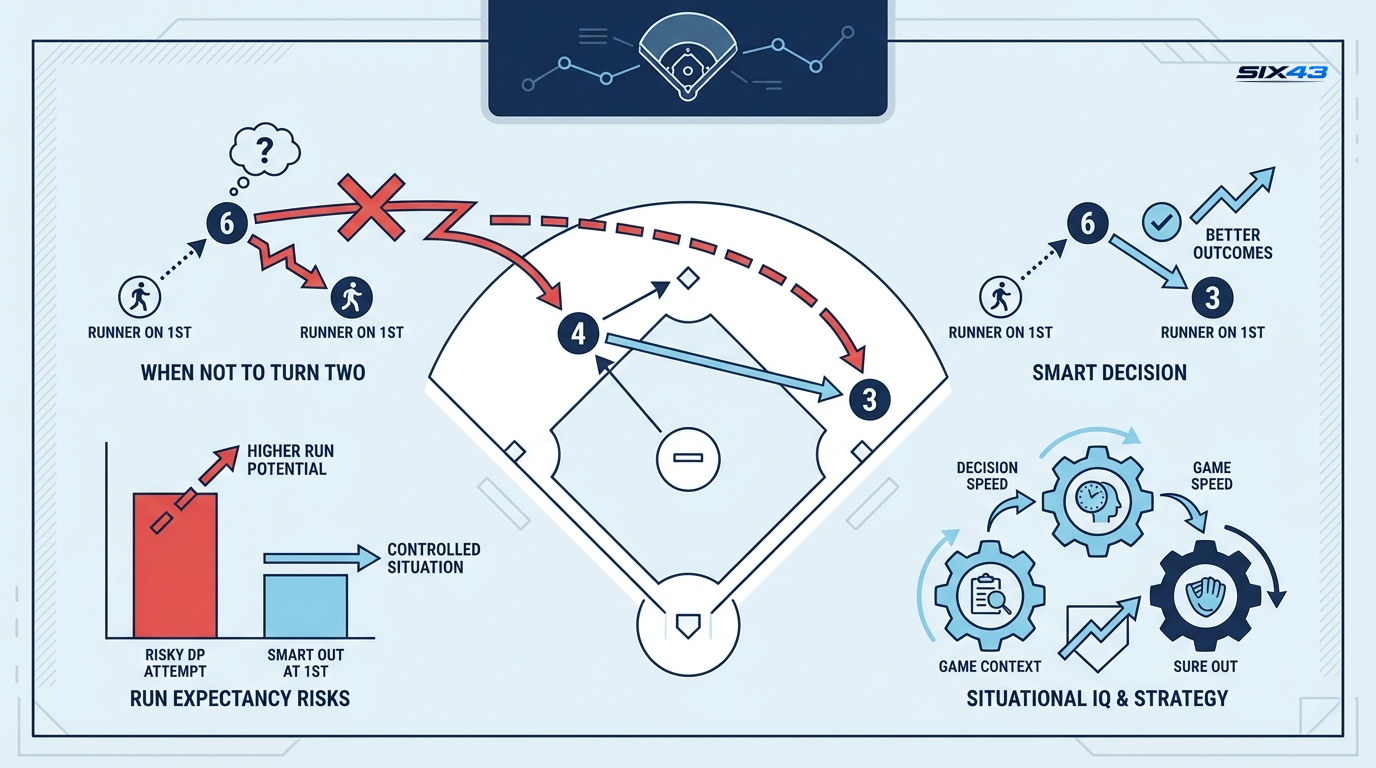

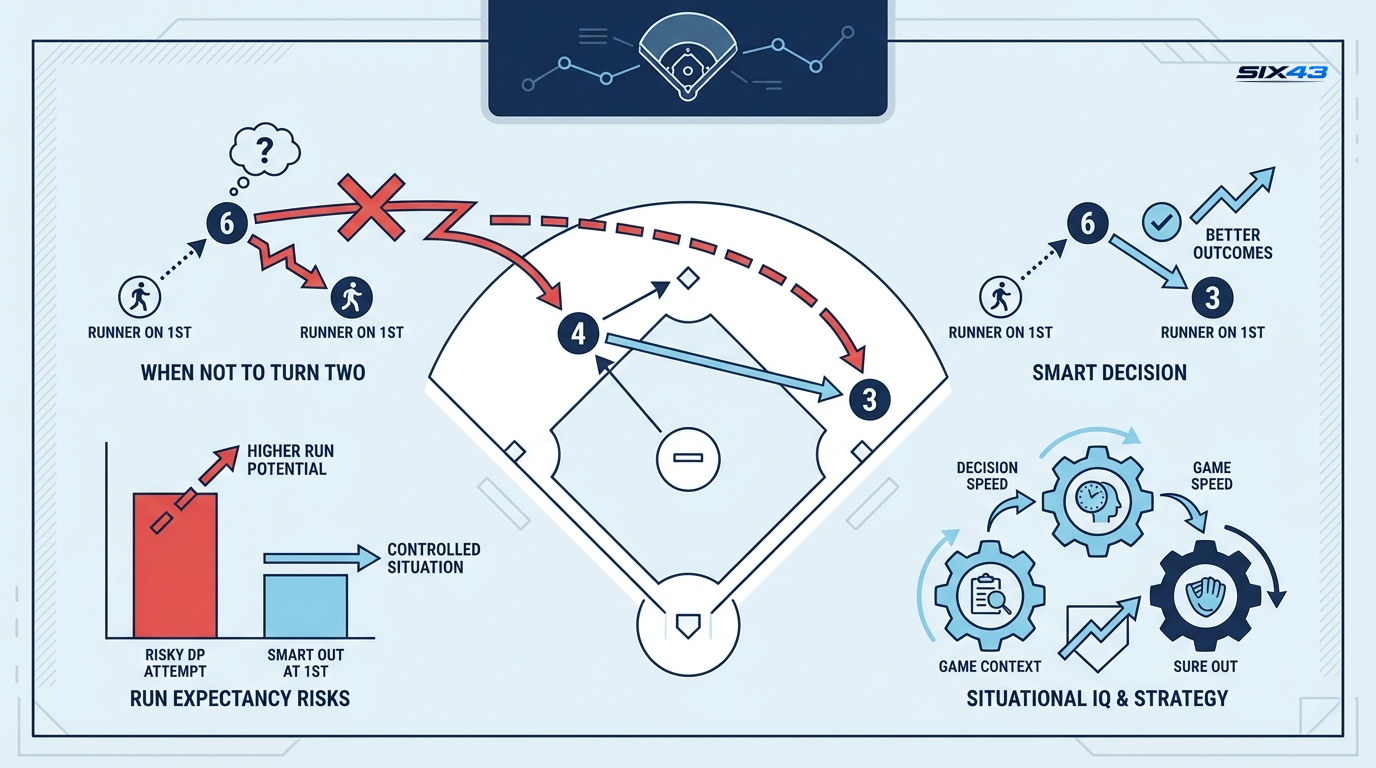

Main idea: In situational baseball, you don’t “always turn two.” You choose the out that prevents the most damage.

Here’s the sticky analogy I use with players: forcing a risky double play is like trying to hit a home run with two strikes when a simple line drive would win the game. The goal isn’t “two outs.” The goal is winning the inning.

At higher levels, double plays are routine because players have the skill package to make them boring:

Youth players are still building that. So double-play attempts carry extra risk—especially when kids start thinking “turn two!” before they secure the baseball. That’s why you’ll hear good coaches repeat the same line all spring:

When the defense gets greedy, the “two outs” dream can turn into:

That’s the real cost: you didn’t just miss a double play—you added chaos.

A lot of double-play trouble starts before the pitch. When the infield is positioned well, players don’t feel like they have to be heroes.

Double-play depth means your middle infielders shade closer to second base than normal to speed up the exchange.

A common youth guideline:

Bringing the infield all the way in too early can backfire:

As coaches, we see this one a lot: the infield creeps in because everyone feels pressure—then a routine ground ball becomes a run-and-runner problem.

Halfway means: not all the way in, not all the way back. For many 10–13U teams, it’s the best of both worlds:

[IMAGE: Infield positioning at “halfway” depth with runner on third, less than two outs — alt text: “Halfway infield depth positioning with runner on third and less than two outs in youth baseball.”]

With bases loaded and <2 outs, youth baseball rewards simple thinking.

Why? Because any mistake is magnified:

In these spots, the high-percentage play is often:

This comes up all the time on a ball to third base: if you’re charging and moving, trying to start a double play to second can be slower and riskier than taking the sure out at the plate.

This is where a lot of parents get surprised.

You’re up 9–1. Bases loaded. No outs.

In that situation, it can be smart to prioritize ending the inning over preventing a single run that doesn’t change the game.

Here’s what we mean (clear and practical):

Youth innings often spiral because:

With a cushion, your best plan is usually:

That’s youth baseball infield strategy: manage the inning like a coach, not like a highlight reel.

A lot of double-play talk assumes a hard-hit ground ball right at a middle infielder.

But in youth baseball, many ground balls are:

When you charge a ball, two things tend to show up:

In those situations, turning two is often a low-percentage bet.

The smart play is usually:

This is a common 12U baseball mistake: kids try to “make the big play” from a bad body position—then nobody gets out.

A fast runner changes everything—especially in leagues where stealing is a big part of the game.

Once the runner steals second, the defense often loses the easy force play at second.

Quick definition (for players and parents):

Important note for youth baseball reality: not every league allows the same stealing rules. In leagues where stealing is frequent, runners who reach first may take second quickly, and once that happens the force at second—and many double-play setups—disappears.

If you face aggressive base running:

That’s how to teach situational awareness in baseball: you plan for what’s likely in your league, not what’s possible in a perfect world.

Even when the ball is fielded clean, the second half of the double play can get messy because of traffic at second.

At the youth level, runners may slide hard—or sometimes just create chaos—trying to break up the turn. That can lead to:

Teach your middle infielders one priority:

Sometimes that means:

Good teams still turn double plays. They just don’t turn them at the cost of extra bases, extra runs, or safety.

To coach this well, kids need contrast: we’re not anti–double play. We’re pro–right play.

A double play is a great choice when most of these boxes are checked:

In other words: when turning two looks “boring,” it’s usually the right time to do it.

This is the part that separates youth baseball strategy from wishful thinking.

Every infield is different. Before you decide how aggressive to be with double plays, assess three things—player by player.

If accuracy isn’t there yet, your “best baseball” may be one clean out.

Watch your middle infielders on feeds:

If footwork is shaky, build confidence with: get one out first, then grow into two.

This is the hidden one.

Some kids are physically talented but slow to choose. If your fielder hesitates, the double play window closes fast—and the rushed throw shows up.

Coaching adjustment:

Baseball IQ isn’t trivia. It’s decision-making under speed.

And youth players can’t scan runners and field a bad hop and run through a mental flowchart.

So keep your language simple.

Try this pre-pitch call:

You’re not scripting the whole play. You’re reducing hesitation.

Because hesitation is where errors live.

Internal link opportunities (use these as consistent anchors across your site):

Want a principle that pays off for years?

Build your defense around this phrase:

When kids believe their job is to get one clean out, you’ll usually see:

Ironically, teams that master “one clean out” often turn more double plays later—because the fundamentals and calm decision-making finally show up.

Double plays are awesome. They’re also one of the easiest ways for youth teams to give away free bases and free runs.

The coaching win is teaching situational awareness:

That’s youth baseball infield strategy. And it’s how you grow baseball IQ in a way that actually shows up on Saturday.

No. With a runner on first and less than two outs, you can prepare for a double play (depth, communication), but you should only force it when the ball is hit hard and clean enough to make it routine.

The best outcome is usually any clean out that prevents a crooked number. In many youth situations, the safest way to do that is taking the out that stops a run right now—often at home.

Because a lot of youth errors happen when a player decides too early, rushes the transfer, and never truly secures the ball.

Usually when you’re up big and you can turn a routine double play—accepting that the runner from third may score while you take two outs and kill the inning.

In leagues where stealing is common, runners may get to second quickly, which removes many force-play double-play chances. In leagues with limited stealing, this matters less.